Growing up, everyone has a favorite board game. Mine was Scrabble. I memorized all the two- letter words and most of the three-letter words. I knew that in a pinch, you could get rid of a pesky Q by playing QAT or QI and that great parallel plays depended on ridiculous Scrabble-only “words” like AA, OE, or UT. But there were other games that I liked less. Sometimes a lot less. Monopoly was probably my least favorite.

Growing up, everyone has a favorite board game. Mine was Scrabble. I memorized all the two- letter words and most of the three-letter words. I knew that in a pinch, you could get rid of a pesky Q by playing QAT or QI and that great parallel plays depended on ridiculous Scrabble-only “words” like AA, OE, or UT. But there were other games that I liked less. Sometimes a lot less. Monopoly was probably my least favorite.

At least my family and friends didn’t have the habit of stealing money from the bank. But the game would always start with miserable inequality and get worse from there – one person would get Baltic and Connecticut Avenues, another would get Park Place and Boardwalk, and a third would somehow end up with all the railroads. Hours would pass as players were slowly forced into debt and mortgages, to be strung along by Chance or Community Chest or Free Parking, but still agonizingly moving towards defeat for all but one.

This was, of course, the point of The Landlord’s Game when Elizabeth Magie first developed it in 1903. The game was intended as a statement about tax policy and the dangers of predacious real estate investors. A bad run of the dice or starting out in a weak position meant that the rest of the game would almost certainly go against you. You can dress it up in anything from Simpsons to Star Wars, but it’s still the same game.

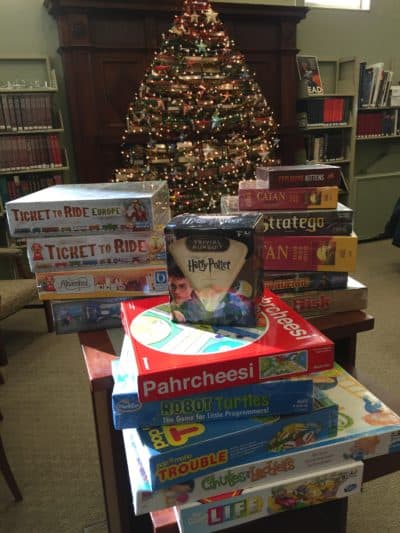

All this being said, no one was happier than I when the library announced that it would be expanding its existing collection of games. Scrabble is fun for me, but if you haven’t prepared, a contest between unequal players can be a bit tough. Other games of skill, like chess or go, have similar problems, while those like Battleship or Chutes and Ladders rely too much on chance to be fun for older players. Many of the library’s new additions are in a style that has become increasingly popular over the past twenty-five years: Eurogames.

I was first exposed to “German Style” board games in graduate school, where I studied medieval history. On a whim, my wife’s mother bought us a copy of Carcassonne, a game created by Klaus-Jürgen Wrede in 2000. Based on the French city of the same name, Carcassonne can be played by any number of players and involves drawing tiles from a bag to create increasingly elaborate city walls, surrounded by winding roads, farmland, and monasteries. Each player can score points in a wide variety of ways and pursue different strategies as the game goes on. No one is eliminated, and it can often be difficult to tell who’s winning until the final tile is drawn from the bag.

Each game has its own theme and complex, but easy to learn, rules. Ticket to Ride asks you to create railroad lines connecting cities across the US or Europe. Alhambra lets you build an Islamic palace in medieval Spain, and Settlers of Catan simulates competition for resources in a new land. Some games have tiles, others involve rolling dice, collecting cards, or purchasing resources. No matter how complex or how many players a game is aimed at, it usually just takes an hour or two to play and can be enjoyable for preteens and adults alike.

Settlers, as it’s frequently called, is the game that really started to attract attention to Eurogames in the United States. Klaus Teuber, a German dental hygienist, spent years developing games with his family as a hobby before he was picked up by a major publisher in the 1990s. Just like a book author, he’s developed a loyal following and fans and critics alike get excited about each new project. Settlers is a great “entry level” game because it still has elements of chance familiar to American audiences – rolling dice every turn – and conflict – you can trade resource cards with other players and gang up on someone who seems to be winning. But the game really stands out with its artistic design featuring an island made up of interchangeable hexagons, each of which is illustrated with a small landscape. Like other Eurogames, another attraction lies in the multiple scoring strategies that can be used: building towns or roads, acquiring resources, trading in materials to recruit armies or founding a school or library! Each player can do something different and still have a chance at winning.

Games like Settlers have players competing indirectly with each other, but others, like Pandemic, actually encourage cooperation. Developed by an American, Matt Leacock, in 2008, Pandemic draws inspiration from the classic board game of Risk. However, whereas Risk features players with increasing numbers of armies and countries striving to eliminate each other, Pandemic gives players a world map where cities are infected with increasing numbers of diseases. Two to six players work together each turn to eliminate cases of infection before they spread and to discover cures. If all the viruses are cured, everyone wins, but there are several different ways for everyone to lose.

All these games, competitive or cooperative, allow more room for socializing and conversation between players. Even if you lose a game, you’ve still gotten a chance to build and strategize, and you can think afterwards about different ways to solve a problem, rather than just wishing you’d rolled better dice. When I first started playing games like Carcassonne and Settlers, they were hard to find except at specialty game stores, stocked between Magic: The Gathering cards and Dungeons & Dragons manuals. Now, stores like Target and Barnes & Noble will regularly stock some of these new classics and toy stores compete to find the next big breakout hit. The US isn’t quite as far along as Germany, where the annual Spiel des Jahres (Game of the Year) prize attracts national media attention, but you should come down to the library, borrow a game, and find out what all the fuss is about!

Jeff Hartman is the Senior Circulation Assistant, Paging Supervisor, and Graphics Designer at the Morrill Memorial Library. Read Jeff’s column in the February 16, 2017 issue of the Norwood Transcript & Bulletin.