This week on October 9, it is the thirty-eighth anniversary of my daughter’s death. I recognize that it can be an unsettling sentence to read. It is shocking for me to write, as well.

This week on October 9, it is the thirty-eighth anniversary of my daughter’s death. I recognize that it can be an unsettling sentence to read. It is shocking for me to write, as well.

Coleen was my firstborn, a daughter born early due to a congenital heart condition that no one suspected until just weeks before her birth. At the time, my ex-husband and I lived outside San Francisco. Two days after New Year’s Day, I was rushed to the University of California-SF Medical Center to await an unknown future. It was new territory for all of us – her father, and I, and our baby. Coleen was born on January 21, 1980, five weeks earlier than her due date.

Her prognosis was never very good from that critical day, and even earlier, according to her new doctors, neonatal specialists and pediatric cardiologists. And yet, she came home to us after a few short months, fragile, yet thriving. On my 28th birthday, when she was four months, a petite and beautiful baby, we were advised that she would not survive infancy. Her terminal diagnosis was the outcome of cardiomyopathy caused by a destructive virus that had also caused illness or defects to other unborn babies in San Francisco. Her right ventricle was acutely compromised by the infection.

We leaned upon our youthful energy and our extended and compassionate family. Our innate optimism commanded us to give Coleen the best life possible for as much time that she with us – and we had with her.

When we lost her, inevitably, one early fall evening in 1981, our lives were rent. I’ve never used that word before, but it comes to me, 38 years later, as a perfect word to describe the brutality of grief that separated us from the before and the after. A storm rents a ship to pieces. A nation is rended by racial upheaval. Our lives were rent by our loss.

Yet, we had our faith, and a new child on the way. We sustained four months of empty arms until life blessed us once again with a second daughter, another beautiful baby girl, this time healthy, with a birthday just two years after our precious Coleen was born. Eighteen months later, another gorgeous daughter was born. Our aching arms and shattered hearts were bursting with that new life. Parents will tell you that practicality takes over after birth, and a quiet, but disordered, grief sneakily hides in the memories and in the shadows.

There is no word in the English language for parents who have suffered the loss of a child. The widow has lost a husband. The widower has lost a wife. The orphan has lost both of his/her parents.

Yet, there is a word for the loss of a child in Arabic (pronounced “thakla”), which translates to bereaved mother. In Sanskrit, there is a word “vilomar,” which means “against the natural order.”

I find this lack in the English language strikingly odd because, over and over, we read and hear that there is no grief like the loss of a child. Yet, we are wordless in our sadness.

Alexander and Eliza Hamilton grieved the loss of their nineteen-year-old son, Philip, when he was shot in a senseless duel in 1801. (Of course, his father sustained the same fate at the hands of Aaron Burr, only three years later.) In Lin-Manuel Miranda’s impressive musical, Hamilton, the song It’s Quiet Uptown holds an emotional grip over anyone who has lost a child. After Philip’s death, the Hamiltons moved from busy Wall Street in Lower Manhattan to a mansion they built in northern Manhattan. It’s Quiet Uptown, a hushed and aching song, describes the anguish of Hamilton and his wife as they walk quietly down the streets of uptown New York, wrought together by their breaking hearts. Passersby watched the newcomers in pity because they realized that the two are “going through the unimaginable.”

Those are the agonizing words. They are the devastatingly simple description. Going through the unimaginable describes the loss of a child.

When I read that Jayson Greene, father of two-year-old Greta Green, had written a book due out last January, I impatiently awaited it. He and his wife Stacy lost their firstborn and only child Greta when she was hit by a falling brick on May 17, 2015, in New York City. Greta was spending the day with her grandmother and sitting on a bench on the sidewalk beneath a high rise windowsill that gave way. It was a freak and impossible accident that immediately changed Jayson’s and Stacy’s lives.

When we lost Coleen in 1981, there were few books to read to help us through our early grief. My library’s shelves and bookstore shelves were bereft of books about surviving the loss of a child. C.S. Lewis wrote of his crushing loss of his wife in A Grief Observed in 1961. Robert Frost wrote of a wife’s devastating grief and a husband’s pragmatic composure after the death of their infant son in Home Burial, one of Frost’s longest and earliest poems. It and other full or partial excerpts were included in Mary Jane Moffat’s compilation of the poetry and literature of mourning. That book, In the Midst of Winter, was published in 1982, just after I was searching for solace in the written word.

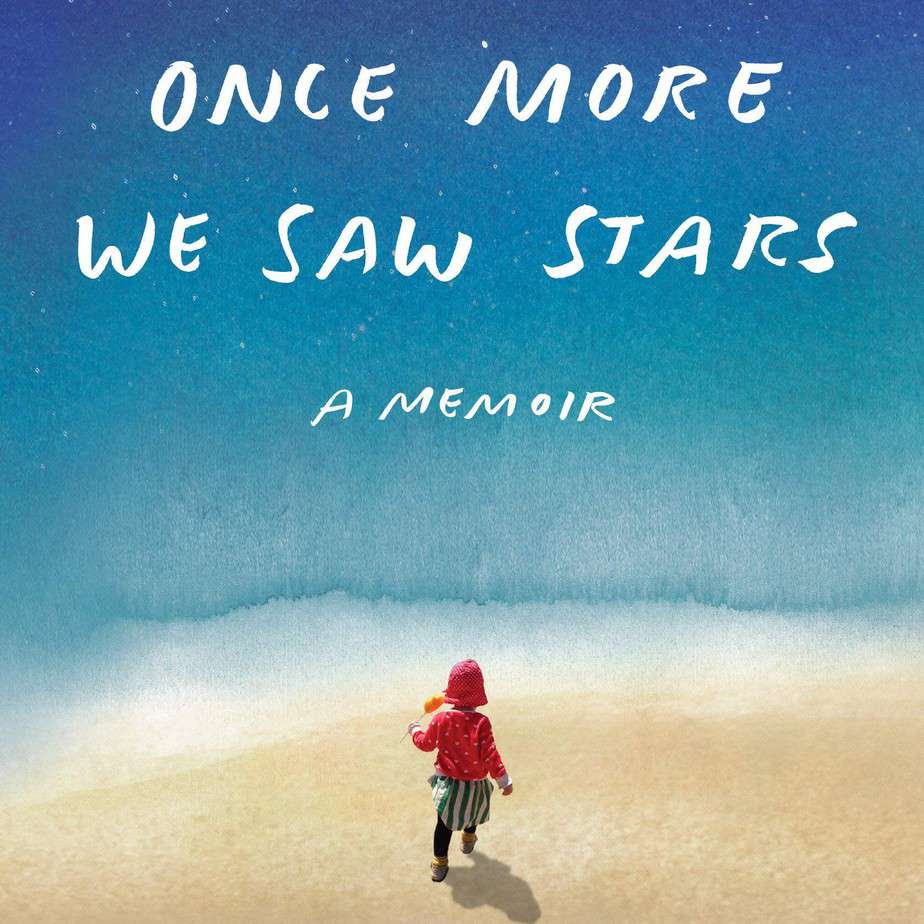

Greene, author of Once More We Saw Stars (2019), writes of his struggle living through a similar time of desolation and despair after the loss of a child. Writing in his journal, Greene described his early grief this way: “I am ice skating along the surface of my shock.” Waking slowly to realization each day, he writes, “What is it? What is it that feels so awful?”

“I remember. I am in hell.”

Jayson and Stacy Greene suffered in the void between being a parent and remaining childless for longer than I did. I had an unoccupied nursery and empty arms for such a short time – only four months. And while theirs, and my life, became whole again, the unfathomable had happened and had changed us forever.

Greene published a New York Times Opinion piece 17 months later in October 2016 following the birth of their second child, a son. He wrote that “life remains precarious,” and he describes the feelings of his children’s precious and fragile lives in Children Don’t Always Live. The title of that piece is raw and jarring, but it defines reality for those who have lived the unimaginable – that of losing a child.

Greene titled his book Once More We Saw Stars as a reference to Dante’s Inferno – that dark time in the dark wood. Climbing out, Dante writes that “To get back up to the shining world from there … through a round aperture I saw appear some of the beautiful things that Heaven bears, where we came forth, and once more saw the stars.”

If you know a family who has lost a child, or you have suffered loss and are looking for words to describe the pain … and reading of faith and hope and survival, read Jayson Greene’s beautiful memoir of his family’s journey through grief. Surprisingly uplifting, Greene’s book writes about “the fragility of life” and the “unconquerable power of love” that will make anyone feel less alone. Perhaps it will be just the right book at just the right time.

Charlotte Canelli is the Library Director at the Morrill Memorial Library in Norwood. Look for her article in the October 10, 2019 issue if the Norwood Transcript.