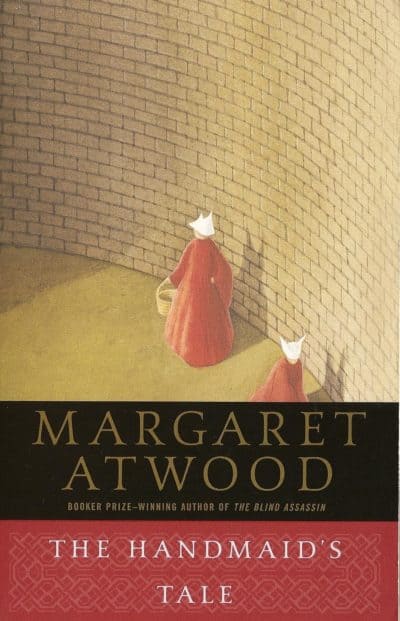

The most common of library problems is requesting one thing and getting something else by mistake. Recently there’s been a recurring issue with patrons finding themselves in possession of a mediocre film adaptation from 1990 rather than a recent hit show. The Handmaid’s Tale is in the public eye at the moment, becoming a successful series on Hulu this year and winning eight Emmys, including those for best drama, best actress, best supporting actress, best writer, and best director. With a prominent career stretching back over fifty years, Margaret Atwood is one of Canada’s best and most-recognized authors. She has won the Man Booker Prize for the best novel published in the British Commonwealth (The Blind Assassin, 2000) and has been shortlisted for four other novels. She has earned the Canadian Governor’s General Prize for Poetry (The Circle Game, 1966) and Fiction (The Handmaid’s Tale, 1985) and has been a finalist on seven other occasions. In addition to accolades in literary society, Atwood is also a major figure in modern science fiction (or speculative fiction, as she prefers to call it) and fantasy, winning the Arthur C. Clarke Award for The Handmaid’s Tale, which was also nominated for the Nebula award in the US, and receiving accolades for Oryx and Crake (2003), The Penelopiad (2005), and The Heart Goes Last (2015).

The Handmaid’s Tale is one of those rare events in film and television that matches or maybe even improves upon the original book. The story envisions a near future where birth rates have fallen dramatically and an extremist religious group takes control of America, forcing fertile women into service for the families of the group’s leaders. Elizabeth Moss portrays one of these women, Ofglen, who has been taken from her husband and daughter and made into a “handmaid” under the threat of torture, expected to provide a child for her master and his barren wife. Atwood and the showrunners explore both the fear and paranoia of the handmaids, who are always under observation, and the bitterness and resentment of the wives, who support this conditional adultery but want the children for themselves.

Both the book and the television show respond to contemporary trends in American (and Canadian) politics that threaten women’s rights to their own bodies. The “Republic of Gilead” takes this to a totalitarian extreme, making it illegal for women to read or write, or to move about the streets of the Boston suburbs unescorted. This imprisonment and imposition of power is central to several of Atwood’s other works as well. Alias Grace (1996) arrives on television in November and looks to the past rather than the future for its titular prisoner. Grace Marks was an Irish immigrant who became a house servant and was then convicted of the murder of her employer in the 1840s. The fictionalized account of her life as told to a psychologist interviewing her reflects on the constraints and pressures that she felt as a working class woman with no legal recourse to protect her from either abuse or poverty.

Two other recent books by Atwood also focus on prisons and the choices people make over the course of their lives that voluntarily limit their options. The Heart Goes Last follows a couple who trade their personal privacy and freedom of movement for the safety and security of a prison compound. An odd romance begins to tear their relationship apart as their constrained lives start to wear on them. Hag-Seed (2017), Atwood’s newest novel, approaches these ideas from the direction of a modern crime story. A failed theater director begins teaching classes at a remote prison and sees his new actors as a means to revenge on those who forced him from the stage. The twist is that the play he is producing as well as the book itself are both modern adaptations of Shakespeare’s The Tempest about the wizard Prospero in exile on a remote island. This is part of a series of books planned by Random House to adapt Shakespearean stories into modern novels of different genres, including Anne Tyler, reimagining The Taming of the Shrew in Vinegar Girl, as well as forthcoming books by Tracy Chevalier, Gillian Flynn, and Jo Nesbø, who will take on Othello, Hamlet, and Macbeth.

Despite the grim nature of some of these descriptions, The Handmaid’s Tale series is an excellent example of how hope and even some humor can be found in even the most desperate situations. Despite the setting of each book, Atwood takes an unflinching look at some of the worst aspects of modern life and then creates characters that can adapt and persist in the face of adversity. As her protagonist Ofglen repeats at her darkest moments, nolite te bastardes carborundorum (“don’t let the bastards grind you down”).

As a refreshing conclusion, Atwood has also recently published the Wandering Wenda series of children’s books about the adventures of a woman and her woodchuck companion and Angel Catbird, a tongue-in-cheek graphic novel featuring a superhero scientist who is part feline and part owl. All of Atwood’s books are available through the library and The Handmaid’s Tale should be out on DVD in the spring.

Jeff Hartman is the Senior Circulation Assistant, Paging Supervisor, and Graphics Designer at the Morrill Memorial Library. Read Jeff’s column in the September 28th issue of the Norwood Transcript and Bulletin.