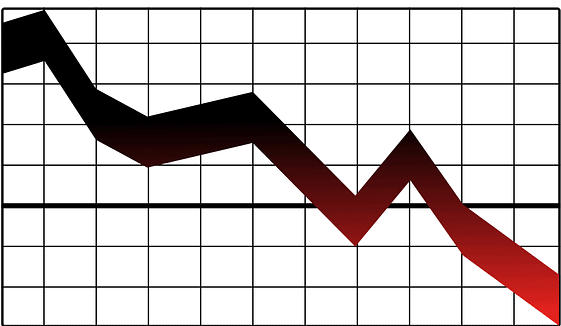

The doctor slid a piece of paper across the table showing a line graph that looked like it represented a stock market crash- a jagged line rising, peaking, falling, then plummeting. The line represented my fertility. She explained the graph with facts, numbers and percentages, but the image of that nose-diving line got the point across. The doctor explained that if I did everything right- took hormones, tracked my ovulation, timed my pregnancy attempts carefully- I’d still only have a 5% chance of getting pregnant, and even if I did, there’d be a 60% chance of miscarriage.

The doctor slid a piece of paper across the table showing a line graph that looked like it represented a stock market crash- a jagged line rising, peaking, falling, then plummeting. The line represented my fertility. She explained the graph with facts, numbers and percentages, but the image of that nose-diving line got the point across. The doctor explained that if I did everything right- took hormones, tracked my ovulation, timed my pregnancy attempts carefully- I’d still only have a 5% chance of getting pregnant, and even if I did, there’d be a 60% chance of miscarriage.

Preliminary tests showed nothing physically wrong with me or my husband. The doctor was essentially telling me I couldn’t have kids because I was just too old. I quickly learned that telling people about the prognosis only made me feel worse. Suddenly everyone had encouraging words about women bearing children late in life. Everyone knew somebody in their mid-forties who had a healthy baby, or someone diagnosed as infertile who wasn’t after all, or a couple who began the process of adoption only to get pregnant soon after. Good for all of those people, I thought, but what about the women who received similar news to mine, and did not go on to have a “miracle” child? I could not count on being one to defy the odds.

In vitro fertilization (IVF), I learned, can cost tens of thousands of dollars and you don’t get a refund if it doesn’t work. Sure, you can’t put a price on your future child’s existence, but librarianship didn’t make me a millionaire, and I could not afford to gamble on getting pregnant through IVF. At that point when I told people about my plight, I started hearing four words I grew to hate even more than those about the miracle babies: “You can always adopt.” Not “usually,” not “potentially,” not “hopefully,” but “always.”

I already felt like a failure because my body could no longer do what the female of the species is supposed to. Now on top of this I was coming to terms with harsh realities and discovering that in a world where “you can always adopt,” my life was in such disarray that I, indeed, could not. I researched adoption options: international, domestic, private, and public through the foster care system. As explained in the UMASS Amherst Center for Adoption Research’s, Adopting in Massachusetts, any adoption requires a homestudy and approval by a social worker. According to the book You Can Adopt, over 90% of prospective parents receive the stamp of approval, but certain factors that signal potential inability to care for a child could rule a couple out.

Truth be told, I did not have a stable home. My husband was in and out of the hospital and the future looked uncertain. Thank goodness the state does not allow just anyone to adopt. Children, especially those already traumatized by birth-family problems and institutional care, need as much stability and security as possible, and in all honesty, I could not provide this. Well-meaning folks again shared stories of unlikely successes. Everyone knew someone who adopted in spite of their age, health, marital status or other factors. But I did not intend to sugarcoat the circumstances to a social worker, trying to make my home life seem less chaotic than it was, or stubbornly persist in getting a child no matter what. The foray into adoption served as a wakeup call. Even though plenty of irresponsible people have children every day, I decided it would be wrong to go out of my way to bring one into my volatile life on purpose.

It took time to accept the new reality and reject the magical thinking others had foist upon me. Going forward I would reluctantly identify as “childless,” which felt pathetic in a world that venerates motherhood, or “child free,” which seemed like a snub toward adults burdened by parenthood and unable to bask in some alleged freedom I must be experiencing. I joined a support group started by Jody Day, author of Living the Life Unexpected: 12 Weeks to Your Plan B for a Meaningful and Fulfilling Future Without Children, and settled on referring to myself as “childless not necessarily by choice.” I met a spectrum of women: some who never wanted kids but found it frustrating navigating life in a society that expects women to become moms, and others whose biology or partnerships thwarted their chances of motherhood.

The best thing the support group offered was a forum for speaking openly about shared experiences. We discussed the dread of going to baby showers, the jealousy we had to hide upon hearing of someone else’s pregnancy, and the frustration of never being taken seriously on topics related to parenting. My childless-by-choice friends tended to revel in the liberty that such a lifestyle avails, and I do appreciate the freedom to travel, stay out late, and make spontaneous decisions without needing to coordinate with a babysitter, however I felt like I was in mourning and not ready to celebrate just yet. My loved ones who had kids tried to elevate me as an honorary part of their families- an Auntie to their kids- but this didn’t help. The other childless-not-necessarily-by-choice women were the people who validated my feelings, and could simply say “I get it, and I’m sorry.”

Ultimately, I experienced a trauma, and recovering from it came from living through it, not being convinced that it didn’t really happen or it wasn’t that bad. We don’t tell people going through a divorce not to worry because the spouse who left will change their mind, or tell people grieving a death that they are better off without the deceased. I had to take time to heal, and still haven’t finished. I stopped going to the support group, but now frequent the website The Not Mom for a sense of belonging among childless women “by choice or by chance.” The website includes an excellent list of books, ranging from the contemplative (Otherhood: Modern Women Finding a New Kind of Happiness) to the humorous (I Can Barely Take Care of Myself: Tales From a Happy Life Without Kids, by Jen Kirkman). The Minuteman Library network has most of the books on the Not Mom list available to borrow in print, audio, or e-book format.

Lydia Sampson is the Assistant Director at the Morrill Memorial Library in Norwood, MA. Look for her article in the January 30, 2020 issue of the Transcript and Bulletin.