I’m here to confess that I’ve never read Frankenstein, the classic work of literature that just celebrated its 200th birthday. I’m guilty of believing some of the myths about the book.

I’m here to confess that I’ve never read Frankenstein, the classic work of literature that just celebrated its 200th birthday. I’m guilty of believing some of the myths about the book.

There are many misconceptions about Frankenstein. First, author Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein’s monster was not a zombie, pieced together and connected by bolts. Nor is he green in color that films and cartoons have portrayed. This eight-foot tall repulsive creature had skin in yellow tones that tightly fit a body of veins and muscles. His eyes glowed, his teeth shone white and emphasized his long black hair and black lips. Most importantly, Frankenstein is not the monster, but it is the name of the scientist who created the monster who was never named in the book.

Mary Wollstonecraft Godwin Shelley was the daughter of philosophers. Her mother Mary Wollstonecraft, an author herself, was one of history’s founding feminists, writing and arguing that women are not inferior to men but women historically lacked the education afforded their male counterparts. Wollstonecraft died only eleven days after giving birth to her infant daughter.

Although her father remarried, Mary felt overshadowed by his two younger children. At the age of 14 she attended a boarding school for six months, however her father’s debt and failed publishing business allowed for no more formal schooling. Mary did have the unique and fortuitous advantage of a homeschool experience in her father’s library. She also traveled with her father during educational trips, and spent much time conversing with his many educated and worldly colleagues. Her father guiltily admitted that while he had not followed the pedagogy of his intelligent and feminist wife who died after childbirth, her daughter Mary received a valuable and complete education.

Mary Shelley conceived of the story of Frankenstein (subtitled The Modern Prometheus) when she was only 18 years old. During a scandalous affair with one of her father’s followers, Percy Shelley, she traveled to Europe and gave birth to a Shelley’s child. It was that rainy summer in Switzerland that their friend and fellow traveler, poet Lord Byron, proposed that they all spend their time writing ghost stories. Wrestling with the idea, Mary imagined a corpse being reanimated. What started as the short story of Frankenstein’s monster was transferred to paper over the next two years.

Percy Shelley and Mary married in 1816 after the suicide of Shelley’s wife. Mary gave birth to two other children but all of her three first children perished soon after birth. In1818, her book Frankenstein was published anonymously and actually thought to be written by Mary’s husband. Her fourth child, born in 1919 was a son named Percy Florence. His birth pulled Mary out of a depression she suffered since losing her infants in 1815, 1816 and 1817.

Her husband Percy Shelley died in a boating accident in 1822 and afterwards Mary devoted her life to writing and raising her surviving son. Although she was famously known for Frankenstein, she did write other successful novels including Mathilda, Lodore and Falkner. The second edition of Frankenstein bore her name as author in 1823.

Reading about Frankenstein, one discovers that while it began as a ghost story contest, it can also be considered a gothic horror story, science fiction, or a treatise of the weaknesses of humans who fool around with science, not understanding the consequences. Frankenstein is horrified at the monster he created in with body parts and electricity in his laboratory. It’s a story of an incredible loneliness, a failed search for companionship, and a terrible knowledge that one can never fit in.

The public radio show Science Friday, aired by over 350 NPR stations, offers seasonal book clubs with conversations, podcasts, and more. This winter’s book club is Frankenstein and participants are reading a special edition annotated “for scientists, engineers, and creators of all kinds.”

There are probably hundreds of editions of Frankenstein that have been published in the past 200 years. The Science Friday choice is a cooperative publication between the Massachusetts Institute of Technology Press and Arizona State University. It is available through the Minuteman Library Network (our library has a copy); however, Arizona State University and MIT have made it available in open access as a PDF (portable document format.) It’s available on the MIT Press website.

The Annotated Frankenstein, edited by Susan Wolfson and Ronald Levao in 2012, is a perfect first reading of edition with illustrations and commentary by professors who have taught the novel. The NEW Annotated Frankenstein edited by Leslie Klinger and published in 2017 features over 200 illustrations and nearly 1,000 annotations. The Graphic Revolve: Common Core Editions published a graphic novel version of Frankenstein in 2014. Frankenstein: The Graphic Novel was adapted for younger children.

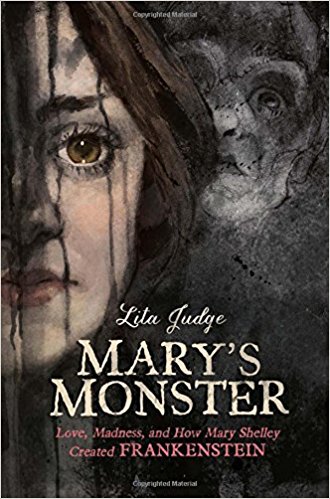

There are over 300 items in the Minuteman Library Network attributed to Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein, including DVDs and non-fiction works devoted to Mary Shelley and her work. The Monsters: Mary Shelley and the Curse of Frankenstein by Dorothy and Thomas Hoobler is a biography of Mary that juxtaposes the tragedies of her life against her success as a writer. A new graphic biography of Shelley will be on library shelves at the end of January: Mary’s Monster: Love, Madness and How Mary Shelley Created Frankenstein by Lita Judge. The book will be a welcome addition to the others with over three hundred pages of black-and-white watercolor illustrations.

The power of Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein is obvious. Shelley’s passions and griefs were transferred into her first, and most famous, work much like the electricity that charged Frankenstein’s corpse to give it life.

Charlotte Canelli is the library director of the Morrill Memorial Library in Norwood, Massachusetts. Read Charlotte’s column in the January 25, 2018 edition of the Norwood Transcript and Bulletin.