Unlike the Ten Commandments that I memorized in Sunday School, I admit that I haven’t been quite as painstakingly thorough with the first ten amendments of our Bill of Rights. I can readily refer to the First Amendment (freedom or religion, speech, press, assembly and petition) and the Second (right to bear arms). Yet, the other eight get a little vague as I search around in my memory for them.

Unlike the Ten Commandments that I memorized in Sunday School, I admit that I haven’t been quite as painstakingly thorough with the first ten amendments of our Bill of Rights. I can readily refer to the First Amendment (freedom or religion, speech, press, assembly and petition) and the Second (right to bear arms). Yet, the other eight get a little vague as I search around in my memory for them.

The Bill of Rights, we all learned in grade school, is the first 10 amendments to the United States Constitution. It was created to protect American public against tyranny from the government they were creating. Simply put, it’s the ten promises that our government has for every one of us from birth to death.

While the Constitution, and all of its 27 amendments, can be a bit wordy at nearly 8,000 words, the Bill of Rights is much shorter at only 452 words. I seems quite easy … yet, so complicated.

The Bill of Rights was written by James Madison in 1789. Several states were a bit worried about individual freedoms and wanted greater protections for them written into the Constitution. Madison proposed 19 amendments on the floor of Congress in June of 1789. Two months later, in September, twelve of the nineteen amendments were approved and sent to the 13 fledgling states for ratification. Madison fought on and debated these changes for two years and finally, on December 15, 1791, Virginia became the last state to ratify the first ten amendments and they became known as the Bill of Rights.

Two of Madison’s approved amendments did not become law – they needed to be ratified by 10 states and they were not. Interestingly, the first was proposed to establish how members of the House of Representatives would be apportioned to the states. While the amendment failed, Article 1 of the Constitution addresses this same topic and by federal statute sets the total members of the House at 435. Interestingly, the second amendment to fail forbade Congress from giving itself a pay raise. This sounds a bit harsher than it is; the sitting Congress could vote a raise but it was only applied to the next Congress. This amendment actually became the 27th amendment to the Constitution in 1992.

Although the Bill of Rights is relatively short, The Bill of Rights Primer (2013) by Amar and Adams is about 400 pages. It’s a thorough book and it explains the concepts of political freedom from the original documents of Thomas Paine’s pamphlet, Common Sense, from the Federalist Papers, and from the guarantees that the American colonies adopted from England. Over half of this stubby guidebook is bibliographical profiles, notes and index, but it is filled with explanations, background, and description of our first ten amendments or freedoms.

In The Know Your Bill of Rights Book (2013) by Sean Patrick, you will read the Preamble to the Bill of Rights. I explains the need for these freedoms. “The Conventions of a number of the States … expressed a desire, in order to prevent misconstruction or abuse of its powers, that further declaratory and restrictive clauses should be added.” It’s a relatively thin paperback, but it includes a glossary and the full wording of each amendment, and an explanation and background of the most controversial ones. The simplest, like the Third Amendment (“No soldier shall, in time of peace be quartered in any house, without the consent of the Owner, nor in time of war, but in a manner to be prescribed by law.”) need little explanation but the First Amendment needs several dozen paragraphs.

The Bill of Rights – the Fight to Secure America’s Liberties (2015) is the second book about the history of the Constitution by Carol Berkin. Another of her books, A Brilliant Solution (2002) focuses on the entire Constitution. This latest book focuses only on the men who battled over the Bill of Rights. It’s a story of ego, argument, and compromise. Berkin’s book contains over 65 pages of brief biographies of the members of the First Federal Congress.

How to Read the Constitution by Paul B. Skousen (2016) includes explanations of all of the amendments, the Constitution, and the Declaration of Independence. It includes memory tricks and small tests, so if you are determined to be the expert at your family dinner table, this is the book for you.

All parents and grandparents can learn more about the Bill of Rights by encouraging small children to begin reading about the Bill of Rights at an early age. There are many books about the entire Constitution, but these focus on the Bill of Rights: America’s Bill of Rights by Kathleen Krull; Scholastic’s The Bill of Rights of Christine Taylor-Butler; and the Fact-Finders series, The Bill of Rights in Translation – What it Really Means by Amie Jane Leavitt. The last two are just the right size for a comfy half-hour conversation on the couch.

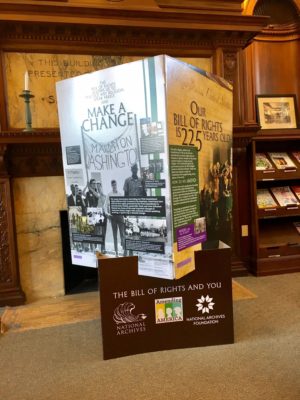

Last year, the National Archives commemorated the 225th anniversary of the Bill of Rights by offering a pop-up kiosk exhibit for local libraries and museums. The deal was that a library would hold a scholar-led discussion or a panel on the bill of rights which was funded by a small $500 grant from the Mass Humanities organization. Many small libraries in Massachusetts participated in this program. We did not apply to be one of them. Why? Because we simply couldn’t decide where the kiosk display would go at the Morrill Memorial Library!

However, when libraries across Massachusetts offered to recycle the kiosk-type exhibits made of cardboard, we hopped on the bandwagon. Or rather, we drove right over to East Bridgewater to pick up their display. That lovely kiosk now sits in front of the Cushing Reading Room fireplace and will during the months of March and April. We think it looks lovely and it reminds us each day that it’s up to us to make the change we need to see as citizens of the United States. It also reminds us how lucky we are to stand behind and beside our 225-year old Bill of Rights.

Charlotte Canelli is the library director at the Morrill Memorial Library in Norwood, Massachusetts. Read Charlotte’s column in the April 20th issue of the Norwood Transcript & Bulletin.