If you study a map of Florida, you’ll see that most of the southern tip is a remote green wilderness with few roads or cities. Except for that significant development of cities and towns along both of Florida’s southern coasts, there are just a few east-to-west highways that connect Boca Raton on the Atlantic to Naples on the Gulf. One of them, Highway 41, starts in a downtown neighborhood in Miami and veers north at Everglades City, bypassing Marco Island, skirts the Gulf Coast cities of western Florida, and then heads north to Michigan. This Tamiami Trail passes east from Miami to the west and north to Tampa. Along the Everglades, it is known as Alligator Alley, with one lane in each direction. Alligators, commonly seen in the waters near the highway, share this land along with hundreds of other animal and bird species.

If you study a map of Florida, you’ll see that most of the southern tip is a remote green wilderness with few roads or cities. Except for that significant development of cities and towns along both of Florida’s southern coasts, there are just a few east-to-west highways that connect Boca Raton on the Atlantic to Naples on the Gulf. One of them, Highway 41, starts in a downtown neighborhood in Miami and veers north at Everglades City, bypassing Marco Island, skirts the Gulf Coast cities of western Florida, and then heads north to Michigan. This Tamiami Trail passes east from Miami to the west and north to Tampa. Along the Everglades, it is known as Alligator Alley, with one lane in each direction. Alligators, commonly seen in the waters near the highway, share this land along with hundreds of other animal and bird species.

A more well-known highway, Interstate 75, skirts the northern parts of the Florida everglades and Big Cypress National Preserve. It travels through Fakahatchee Strand State Preserve before it, too, turns north through western Florida, before it reaches West Virginia forests and eventually crosses the land between the Great Lakes and ends at the Canadian border.

Most travelers take either of these two routes across the vast glades of Florida. The hardier traveler, however, travels southwest from Homestead, passing through Everglades National Park along State Highway 9336 and deep into the swamp at the southernmost tip. Those riskier adventure-seekers can then go to the ghost town of Flamingo, or travel along the 99-mile Everglades Wilderness Waterway. This watery land is also known as the Marjory Stoneman Douglas Wilderness. It is only accessed by kayak, canoe, and shallow-draft powerboats through a system of interconnected creeks, rivers, bays, and lakes. It is recommended that boaters relying on paddles plan eight days to travel – one of the passes is navigable only at high tide.

The Florida Everglades was originally a 14,000-square mile expanse. Through a series of diversions, the Everglades has shrunk to 4,000 square miles. The 1.5 million acres known as Everglades National Park protects the 20% of the original area.

While most of America’s national parks are established to preserve the beautiful and unique geography of the United States (such as Yellowstone, the Grand Canyon, Death Valley) the Everglades National Park was created to protect a fragile ecosystem. Lake Okeechobee to the north feeds a river that flows through the glades into Florida Bay. I had always envisioned the Everglades as a dark and murky, wet and wild place much like a rain forest. Instead, I have learned it is a flowing river and provides a perfect habitat for the American crocodile and other reptiles such as alligators and snakes, the Florida panther, the West Indian manatee, 350 species of birds and hundreds of types of fish.

In 1882 the first plans to drain these Florida wetlands began as somewhat well-intentioned uses for agricultural and residential development. At that time, Miami was merely an eastern outpost. Once a land inhabited by the Tequesta – a Native American tribe that occupied this area along the southeastern Atlantic coast – missionaries and colonists were attracted to the land and its long growing season. When railroad tycoon Henry Flagler connected the Florida East Coast Railway to Miami, the population of the town was a bit over 300. After World War II, Miami’s population soared to nearly 500,000, similar to what it is today. However, the northern and southern metropolis of Miami boasts over 6 million residents, the seventh-largest in the United States.

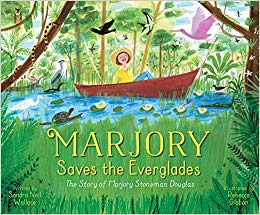

Fortunately for Florida, environmentalists intervened well before this population boom to protect the vanishing Everglades. The foremost of those was Marjory Stoneman Douglas.

Many of us are familiar with the name Marjory Stoneham Douglas. On Valentine’s Day two years ago, a deranged gunman killed 17 children and adults at the Marjory Stoneman Douglas High School in Parkland, Florida. That school had opened on Douglas’ 100th birthday in 1990. An elementary school in Miami-Dade County is also named after her, along with a municipal building, and a 15-minute orchestra piece, Voice of the Everglades. But, there is so much more to attribute to Douglas, including saving the Everglades.

Marjory Stoneman Douglas has roots in New England that I never knew about until my Everglades reading began. While she was born in 1890 in Minneapolis, after the divorce of her parents at age six she moved to her mother’s family home in nearby Taunton, Massachusetts. At the age of 17, she won a Boston Herald prize for a short story. A stellar reader, writer and student, she left home for Wellesley College at the age of eighteen and graduated in 1912.

Several years later, after the death of her mother, (and a failed marriage to a scoundrel named Kenneth Douglas) she moved to Florida. There she began writing for a newspaper that her father published – later to be named the Miami Herald. It was through her journalistic voice that Marjory began changing the history of Florida.

Her early activism included women’s suffrage and public health. Her efforts turned to environmentalism early in the 1920s when she was in her thirties when she joined the board of the Everglades Tropical National Park Committee. In 1947, she wrote The Everglades: River of Grass, the essential book written about the Everglades.

The story of Florida, the terrible mismanagement of natural resources, the Big Sugar pollution of Lake Okeechobee, the rampant abuse of the land, and the corruption of politicians, is a larger story than this column can begin to describe. Yet, the work of Marjory Stoneham Douglas has saved a portion of the Florida Everglades for generations to enjoy.

If you are interested in learning about this magical wilderness and its rescue, read The Swamp: The Everglades, Florida, and the Politics of Paradise (2007) by Time correspondent Michael Grunwald. In another great book, Liquid Land: A Journey through the Florida Everglades (2004), author Ted Levin describes his many journeys through the Everglades, with profiles of those who attempted to coerce or steal the Everglades for development – and those who have worked to win it back.

If you want a serious, and sometimes hilarious, account, read Hodding Carter’s Stolen Water: Saving the Everglades from Its Friends, Foes and Florida (2005). It’s a great way to begin an education into the story of Florida and the abuse of its land, particularly the Everglades wilderness.

Jack E. Davis’ biography of Marjory Stoneman Douglas, An Everglades Providence (2009), is a 700-page tome dedicated to the virtues and actions of this amazing woman. In 1993, five years before her death at age 108, Marjory was awarded the Presidential Medal of Freedom, the highest civilian honor granted by the United States. The citation read “Grateful Americans honor the Grandmother of the Glades by following her splendid example in safeguarding America’s beauty and splendor for generations to come.”

A lovely children’s picture book biography will be published this September. Marjory Saves the Everglades will be an important book to share with every young environmentalist. As Marjory and other preservationists cry, “The Everglades is a test. If we pass, we get to keep the planet.”

Charlotte Canelli is the Director of the Morrill Memorial Library in Norwood, MA. Look for her article in the February 13, 2020 issue of the Transcript and Bulletin.