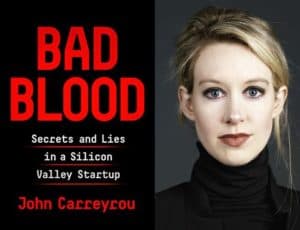

The saga of Elizabeth Holmes and Theranos, her revolutionary (but failed) blood testing company, is a captivating one. While you may have read about it on the Internet, or in news reports last summer, you should read the exposé, Bad Blood by John Carreyrou, published last fall. It is rich with the full account as it was revealed. Carreyrou was (and is) a reporter for the Wall Street Journal. He was hungry for his next new journalistic journey, and a tip about Theranos was just the ticket.

The saga of Elizabeth Holmes and Theranos, her revolutionary (but failed) blood testing company, is a captivating one. While you may have read about it on the Internet, or in news reports last summer, you should read the exposé, Bad Blood by John Carreyrou, published last fall. It is rich with the full account as it was revealed. Carreyrou was (and is) a reporter for the Wall Street Journal. He was hungry for his next new journalistic journey, and a tip about Theranos was just the ticket.

The story of Theranos begins with Elizabeth at 19 – a college dropout – and a concept that depended on all the stars aligning and the pieces of the puzzle falling into place. Most importantly, however, science was required to work.

Detractors have declared that the science was never there to begin with. That it was an absurd quest. Others question if more years and engineering may develop the product that Elizabeth promised – a piece of medical equipment that can deliver accurate results of over 1000 separate tests using only a finger-prick and one drop of blood. Theranos bombed miserably, but not before duping investors and the public.

For those of us hungry for a tragic tale – one that includes billions of dollars and an abundance of Silicon Valley garish living habits, the story does not disappoint. And further, there are continuing acts of trickery, meaningless investments, and the clandestine romance of the two ambitious, vital players.

If you are further intrigued, the HBO documentary, The Inventor: Out for Blood, is an excellent way to watch Elizabeth Holmes in action. It is full of both stills and video that explain some of Elizabeth’s appeal. More importantly, the documentary is full of interviews and testimonies with the whistle-blowers, the detractors, and some of the people who finally began to suspect that Theranos was essentially a house of cards ready to fall. (The HBO documentary is available in several outlets; I found it offered free on a JetBlue flight. Be assured that we will purchase the documentary when it is available on DVD.) Some of Holmes’ charm (whether you find her alluring or not) is explained in the video; at least it is obvious by the men who were beset with her.)

Another, somewhat abridged version of the story is the fascinating six-episode (free) podcast, The Dropout (produced by ABC Radio and ABC News Nightline.) It’s under five hours of listening and rich with the voices involved in the scandal. I listened to the podcast before reading the book; the book is a richer telling of the Theranos tale. I described the podcast as abridged because there are details in Carreyrou’s book that answered many of the questions I had that were left unanswered by the podcast.

The documentary and the podcast left me wanting more. There are hundreds of news articles written about Theranos, both in the ascent of Elizabeth Holmes and in her tragic downfall. In addition, there are short videos and teasers for the documentary.

Many people can’t wrap their head around the magic spell Elizabeth Holmes presented or staged to enchant men like statesmen George Shultz and Henry Kissinger, investors like the Walton (Walmart) family, Rupert Murdock, and Betsy DeVos, and business partners like Walgreen’s. But she did. And easily. They were all hopelessly smitten by the young woman, or by the recommendations of people in high places. For a period of 14 years, Holmes managed to defraud millions of dollars in investments for her Silicon Valley start-up, much of it from Walgreen’s, the pharmacy “trusted since 1901.”

Some of Elizabeth Holmes’ biographical history explains her rise to fame. She was smart. She was pretty. She was ambitious. As a young child, Elizabeth was attracted to both fame and fortune, and she dreamed of becoming recognized for inventing something that would change the world. Some have suggested that her biggest aspiration was to become a billionaire.

Those who interacted with Elizabeth in the classroom or neighborhoods she lived in seemed to be either dazzled or unimpressed by Elizabeth’s poise, composure, and can-do attitude. She was enabled by a family who encouraged her and who had some critical connections through their work and lifestyle. She lived in both Washington, DC and Houston and was afforded splendid opportunities such as summer Mandarin language programs in China. She had no difficulty being accepted to Stanford as a freshman in 2002. By 2004, at the age of nineteen, she dropped out of college, mainly because she was spending more time presenting her ideas to venture capitalists and to influential contacts and wealthy families than she was spending on her studies.

Elizabeth amazingly succeeded in getting her advisor and the Dean of the School of Engineering, Channing Robertson, to join her in her effort to “revolutionize healthcare.” Other influential men in the heart of Silicon Valley, particularly with ties to big money were also impressed, and they all helped her in her spectacular rise. Of note, however, is that none of the investors and board members influential in Holmes’ rise were engineers or scientists. Just like those who knew her as a child, not everyone was charmed with Elizabeth or her company. She had detractors along the way. Many Silicon Valley stars quickly left her company, and some became whistle-blowers. One became so disheartened that he took his own life.

The story of Theranos is actually ongoing, even though the company ceased to exist in 2018 after a three-year investigation by the SEC and others. Elizabeth, the woman who yearned to be the next Steve Jobs, is facing criminal charges of up to 20 years in jail, along with her one-time lover, Ramesh (Sunny) Balwani. The real tragic end may come later this summer after the trial is over.

Charlotte Canelli is the Director of the Morrill Memorial Library in Norwood, MA. Look for her article in the May 9th issue of the Norwood Transcript.